| 13-11-2018 | François de Witte | TreasuryXL |

1. Purpose of payments

The payment is the act of paying money to someone or of being paid. Payment transactions (payables, disbursements) can traditionally be split along the way the way the money is transmitted. The most important transmission means are:

- The physical cash

- The bank transfer and its variances

- The card payments.

We have also observed in the last years new payment forms coming up, such as the telecom payments, the mobile payments, e-wallets and the cryptocurrency payments,

Bank transfers (and its variances) can traditionally be split in:

- Domestic transfers: payments within a country, with the currency of the country

- Cross-border transfers: payments outside the country or using a foreign currency

In this first article on payments, we will focus on the domestic bank transfers, including the current types payments, their advantages and the attention points, and some other concepts.

2. Domestic Transfers

2.1. Bank or Credit Transfer:

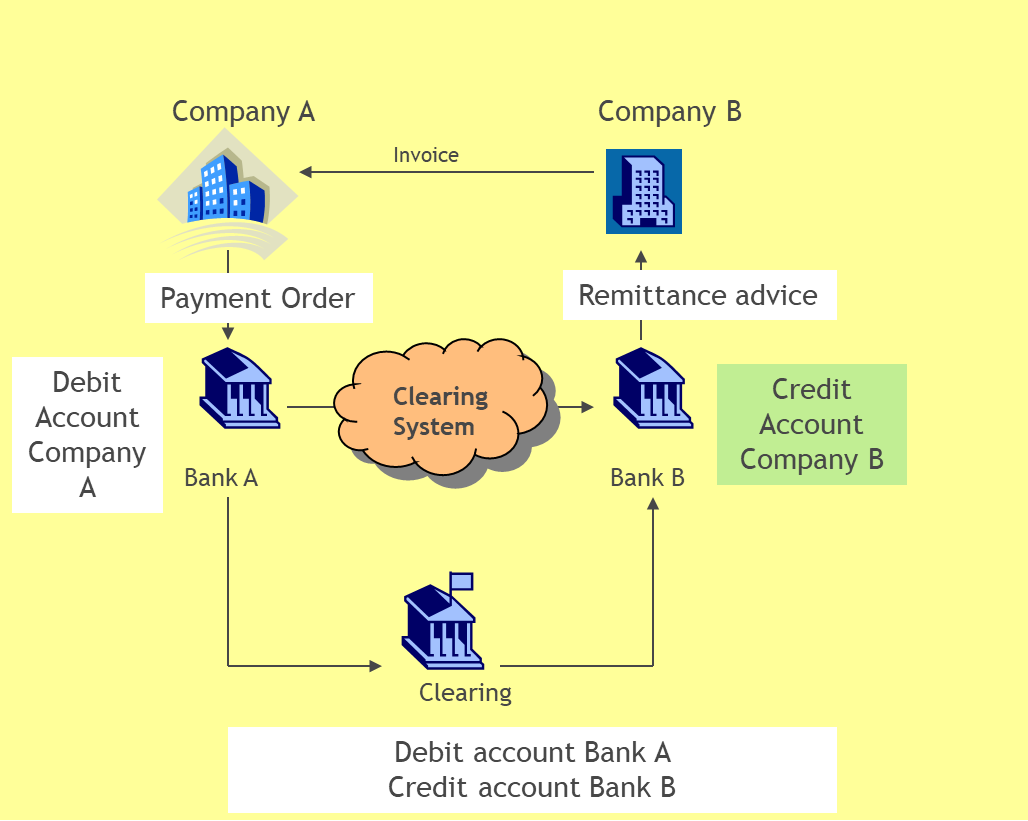

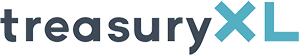

If A needs to pay money to B, then he will send a payment order to his bank (ordering bank), who will in turn debits the account of company A and sends the payment order to bank of the beneficiary (B’s Bank) through the clearing, asking to B’s bank to credit the beneficiary’s account.

The following drawing illustrates the flows:

2.2 Clearing:

Clearing is the system, by which an organization (the clearing house) acts as an intermediary in a transaction, to process reconcile orders between paying and receiving parties. Clearing houses provides smoother and more efficient payment markets as parties can make transfers to the clearing house rather than to each individual party with to whom they pay or from which they receive payments.

Within payments we have the difference between the gross and the net settlement:

- Net settlement (also known under the name ACH – Automated Clearing House): This is the traditional Approach, whereby the amounts to be paid and received are netted. After agreed upon clearing cycles, the clearing house will pay a net amount to each of the participants, offsetting incoming and outgoing payments. The advantage of this clearing is that it is processed in batch payments and is less expensive. The drawback is that the finality of the payment is only at end of “clearing period”, and that it creates intra-day exposures.

Examples: UK cheque clearing, BACS, ACH in USA, EBA Step 2 and STET for SEPA payments

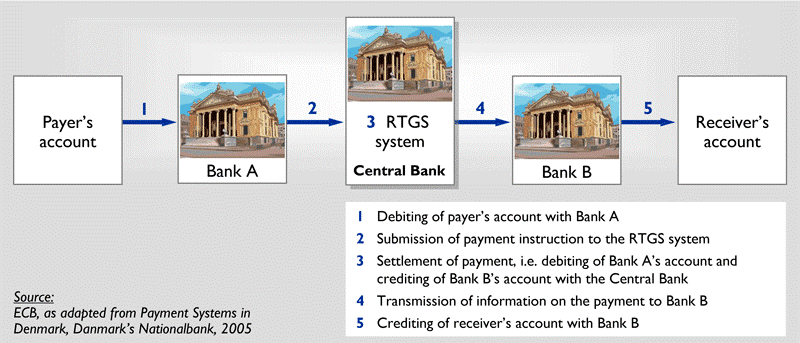

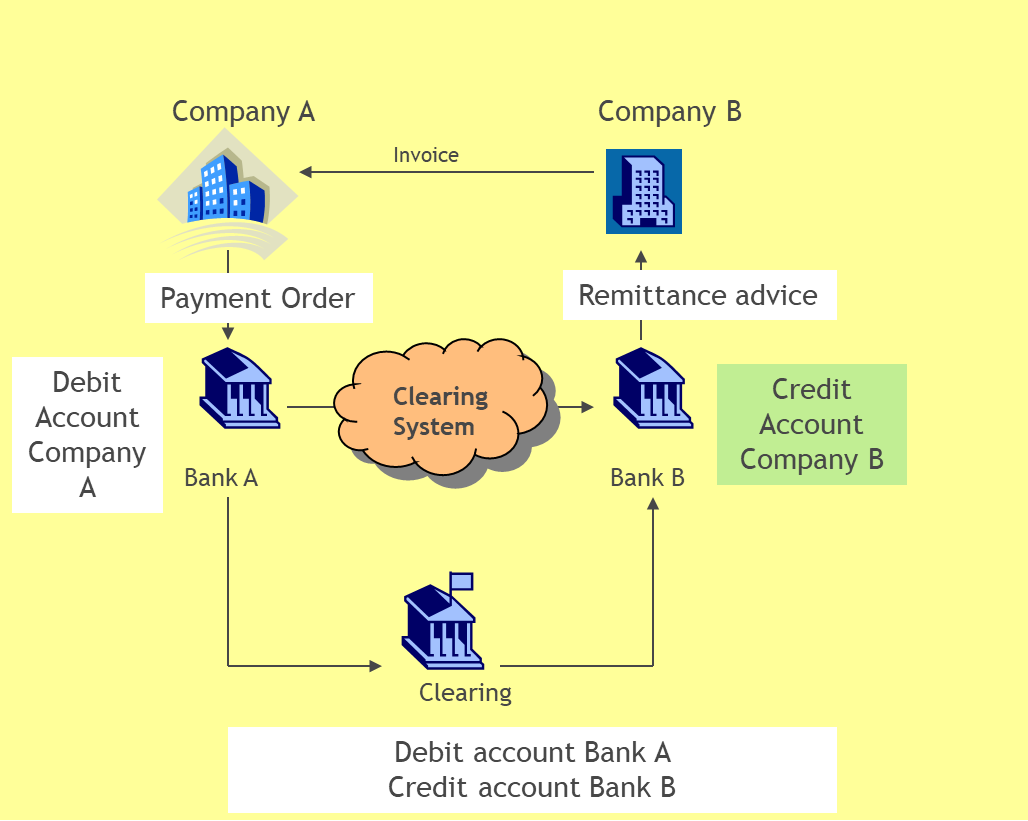

- Gross settlement (also known under the name RTGS – Real Time Gross Settlement): Each payment settles singly and bilaterally across accounts at the settlement bank, usually the central bank. The advantage of this method is that it is more rapid and eliminates settlement risk. However, it is more expensive than the ACH clearing, and hence will be used more for high value and treasury payments.

Examples: Fedwire in the USA, CHATS in Hong Kong, TARGET in Europe, CHAPS in the UK, DEBES in Denmark, RIX in Sweden and SIX in Switzerland

Illustration of the RTGS system:

2.3 Standing order (also called “recurrent payment”):

This a preauthorised payment under which an account holder instructs his bank to pay on a regular basis a fixed amount from his account to a defined beneficiary. Standing orders are used typically for recurring, fixed-amount expenses (e.g. rental payments, loan or mortgage instalments). They are cancellable at the accountholder’s request.

2.4 Direct debit: Direct Debit:

This is another type of preauthorised payment under which an account holder authorizes his bank to accept debit instructions on his account towards a defined account of a defined creditor. A direct debit is based upon a mandate which is held either by the bank of the debtor or by the creditor. Circumstances in which the funds are drawn as well as dates and amounts are agreed upon between the payee and payer.

This type of payments is typically used for recurrent payments with fluctuating amounts, such as utilities, phone, insurance, credit cards, etc. The payer can cancel the authorization for a direct debit at any time. In addition, several legislations foresee refund periods, enabling the account holder to ask a refund of the amount debited from his account (in the EU for authorized direct debits 8 weeks and for unauthorized direct debits 13 months).

2.5 Urgent versus non urgent-payments:

Most payments are processed as “non-urgent”, enabling the instructing bank to process the payment in batches through the ACH clearing and to take some float. However, for time critical payments, the instructing party can as to his bank to treat the payment order as “urgent”. Urgent payments are usually cleared through the RTGS clearing. If the ordering party respects the cut-off time of his bank (see down below), for domestic payments, the beneficiary is credited the same day with no float. Banks usually charge a higher payment commission for urgent payments.

2.6 Instant credit transfers:

Are a variance of the urgent bank transfer, whereby the money is made available within seconds on the account of the recipient, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. In some countries, this is already possible.

Example: SEPA Credit Transfer Instant, Faster Payments Service in the UK, The RTP system which will be launched early 2019 in the US.

3. Some other concepts:

Settlement date is the date on which funds become unavailable for the paying party, or available to the beneficiary party.

Value dating: applying a certain value date on a transaction:

- Forward value dating (of Future dating): is the value dating at a moment which occurs after the date that the bank is notified of the transaction

- Back value dating: is value dating which is retroactive, i.e. prior to the moment of the effective transaction.

Float: the “Bank Float” is the time that elapses between the moment that the funds are unavailable funds for the payer and the moment that the funds available to the beneficiary.

Cut-off time for payments: the point in time before which electronic payments, such as a RTGS or ACH payment, must be submitted to a processing bank for entry into the interbank clearing system. If the payment order is submitted thereafter, it will be executed the next day. The cut-off time is a function of the cut-off time of the clearing system and of the processing time of the ordering bank. In Europe, most banks foresee cut-off times around 15 p.m. for processing ACH or RTGS orders.

4. Some statistics and concluding remarks:

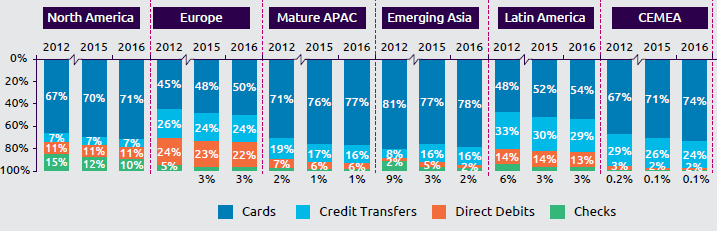

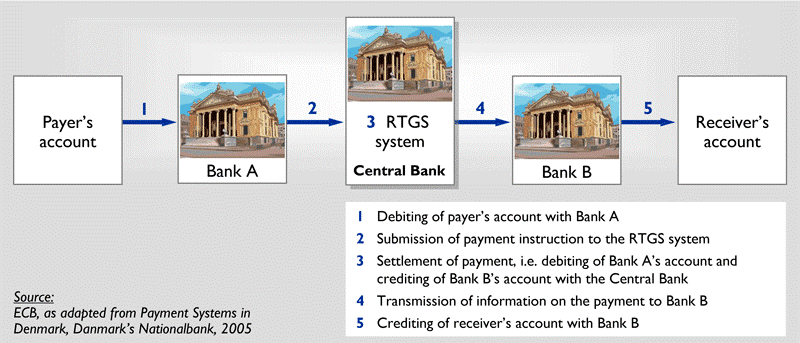

Each year, Cap Gemini and BNP Paribas publish a survey with interesting statistics about payment methods in the world. In their 2018 survey they point out that whilst credit transfers and direct debits remains important in Europe (46 % of the non-cash payment volumes), we see that card payments are becoming more and more important (50 % of the non-cash payment volumes in 2016).

Source: Cap Gemini and BNP World Payments Report 2018

In my next contribution I will go more in detail in the card payments and on cross border payments.

François de Witte

Founder & Senior Consultant at FDW Consult

Managing Director and CFO at SafeTrade Holding S.A.

Roy Baaten – Community Manager at TreasuryXL

Roy Baaten – Community Manager at TreasuryXL