Davos, interest rates and secular stagnation

| 08-02-2018 | Lionel Pavey |

Two weeks ago there was the annual meeting of more than 2,000 politicians, business people, economists etc. at the World Economic Forum. For 4 days the most pressing and urgent topics facing the world were discussed. Sifting through all the speeches and press statements, I saw a lot of articles relating to a rather old theme of secular stagnation.

What is it?

It is a theory dating back to the 1930s stating that developed countries can suffer from a period of too small investment and too large savings. This can be the result not only of an economic recession but, more importantly, as the result of changes in the underlying demographics within a country. This would in turn imply that growth would be low to negligible within the economy. As growth slows down, so demand for investment would also slow down, leading to more savings etc.

Normal theory would demand a reduction in interest rates (the cost of money) leading to an increase in long term investments by companies, a comparative feeling of wealth amongst the people and a kick start to the economy.

Since the crisis of 2008, we have experienced an extended period of low interest rates and low inflation. The expected increase in investment, leading to improved production processes and new goods does not appear to have materialised. Furthermore, the effect that the crisis has had on individual people – job losses, house repossessions, insecurity – has made them reticent to indulge in large bouts of consumer spending.

Even with negative interest rates there has been no rush to invest in productivity. Instead funds are invested in financial assets – shares, bonds etc. Whilst offering goods returns, such investments do not add to potential economic productivity and growth in the industries that provide it.

Furthermore, when consumers tighten their belts – restricting spending and increasing savings – they are not actually directly providing funds for investment. Banks operate as intermediaries and extend credit – individual investors do not in the present system.

The economy is growing – GDP forecasts are all up among the major developed countries and inflation appears to be restrained. So have we broken the long existing chain of recognised monetary theory – could we see a prolonged period of steady growth, backed by low interest rates and low inflation?

At this stage of the proceedings an added element was thrown into the debates – demographics.

Europe is experiencing a period of shifting demographics. The long term replacement fertility rate is 2.1 children per woman. There has been a steep decline of this rate within Europe, with the rate in Germany being as low as 1.4 children. At the same time people are living longer, which means they are retired for longer. In 2006 there were 4 active workers for every retiree – by 2050 this could be down to only 2. The median age in Europe is expected to rise from 37 to 52 by 2050. EU studies have forecast that by 2050 there will be a reduction of 48 million in the working age population and an increase of 58 million in the retirees.

At the same time other studies suggest there will be a 14% decrease in working population against a 7% decrease in total population. All these projections are based on the current situation and that the trend continues.

If this was to continue, then there would be significant challenges for Europe. The expectation of governments to be able to finance the existing outstanding debt by increases in national GDP will stall. Increased burdens will be placed on the state to provide the necessary facilities to an ageing population whilst the pool of available workers is shrinking, leading to lower productivity per capita. Within the last 10 years the distribution of wealth has been skewed – there is more inequality with the super rich having proportionally even more of the total wealth than before the crisis.

New technology has the ability to change the existing concept of productivity. However, if this could be more than enough to offset the expected developments caused by an ageing population is unclear. It could mean that we are entering a prolonged period of low interest rates, low inflation and low growth. If so, all the economic models – even within companies – will need to be reappraised and a new long term policy initiated.

Cash Management and Treasury Specialist

Over the last year there have been impressive price gains in Greek Government bonds leading to equally impressive falls in yields. Greek 2-year bonds are now yielding 1.35% – down from around 7% at the start of 2017. Similarly, 10-year bonds are now yielding 3.66% – a significant fall since the start of 2017. In fact, the yield on Greek 2-year bonds is now lower than in USA where the current yield is 2.09%. Last week S&P upgraded Greece’s long term credit rating to ‘B’ from ‘B-‘. It would appear that Greece is doing everything right. Right?

Over the last year there have been impressive price gains in Greek Government bonds leading to equally impressive falls in yields. Greek 2-year bonds are now yielding 1.35% – down from around 7% at the start of 2017. Similarly, 10-year bonds are now yielding 3.66% – a significant fall since the start of 2017. In fact, the yield on Greek 2-year bonds is now lower than in USA where the current yield is 2.09%. Last week S&P upgraded Greece’s long term credit rating to ‘B’ from ‘B-‘. It would appear that Greece is doing everything right. Right? Despite interest rate being very low for the last few years, general consensus is that rates will eventually rise – rates will become more normal. Rates are being held down by the actions of central banks with their quantitative easing. As QE is scaled backed and stopped this should allow rates to rise from their current low levels. The big question is – how high will rates rise? The Euro is not yet 20 years old and that means that whilst there is a lot of data, it does not require looking through 50 or 60 years of data to try and find the norm.

Despite interest rate being very low for the last few years, general consensus is that rates will eventually rise – rates will become more normal. Rates are being held down by the actions of central banks with their quantitative easing. As QE is scaled backed and stopped this should allow rates to rise from their current low levels. The big question is – how high will rates rise? The Euro is not yet 20 years old and that means that whilst there is a lot of data, it does not require looking through 50 or 60 years of data to try and find the norm.

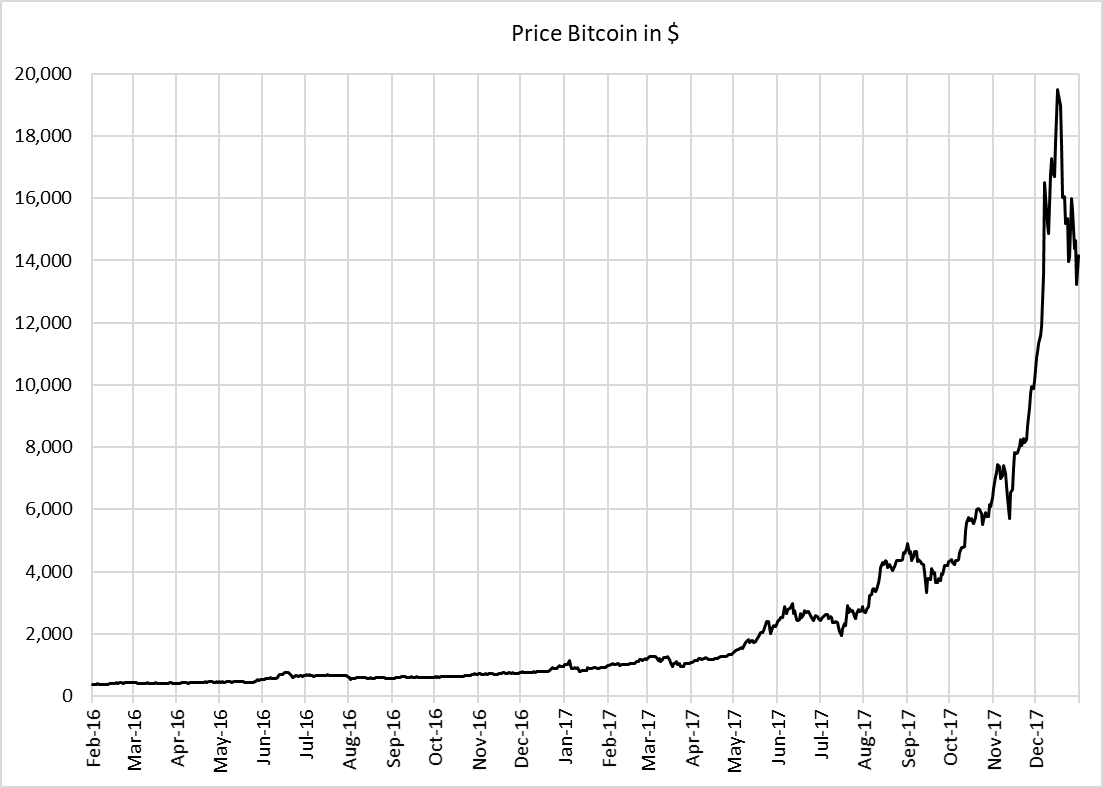

Having spent my working life in international finance, I have patiently listened to all the news about the Bitcoin over the last few years. During 2017 whilst the Bitcoin was on a spectacular price rise, my interest was awakened in this new phenomenon – is this the future? I attended seminars, read articles, learnt the difference between the Bitcoin and the Blockchain, searched and investigated via the web, and tried to form an opinion. These are my findings:

Having spent my working life in international finance, I have patiently listened to all the news about the Bitcoin over the last few years. During 2017 whilst the Bitcoin was on a spectacular price rise, my interest was awakened in this new phenomenon – is this the future? I attended seminars, read articles, learnt the difference between the Bitcoin and the Blockchain, searched and investigated via the web, and tried to form an opinion. These are my findings: Such a stellar performance should mean that the trade volume has increased dramatically.

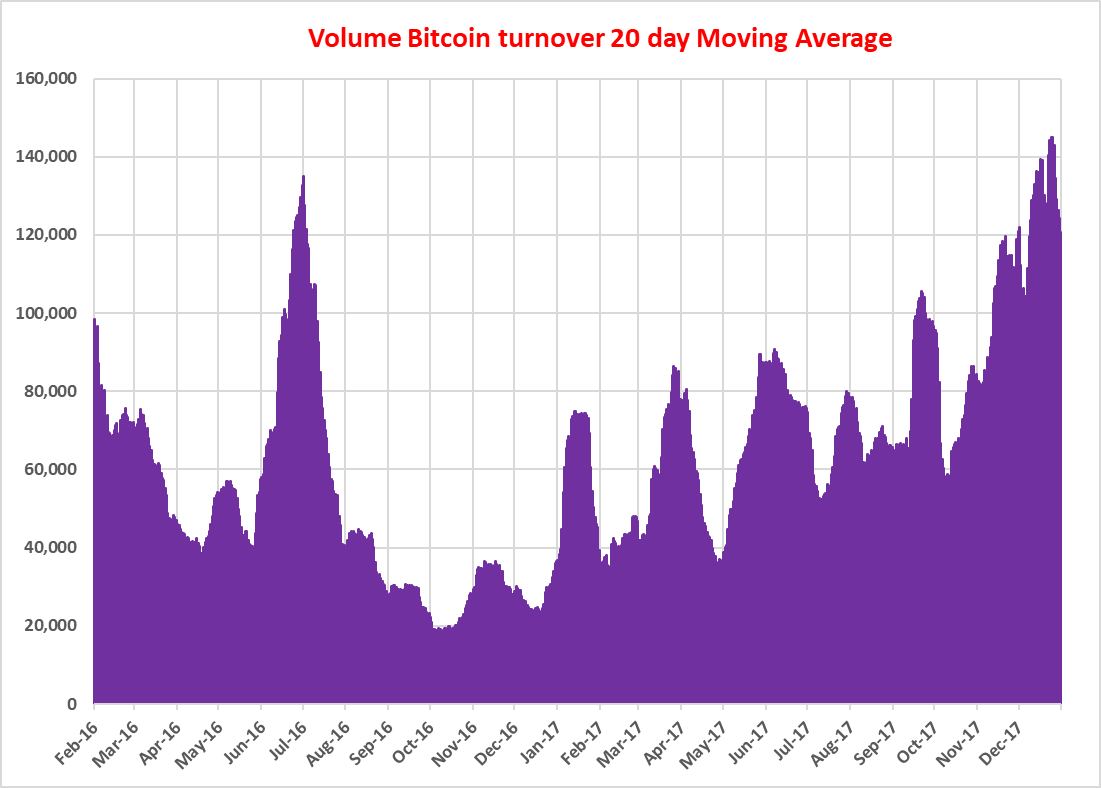

Such a stellar performance should mean that the trade volume has increased dramatically. The daily volume in September 2017 when the price was about $4,000 was the same as the start of February 2016 when the price was about $400. I had to create this chart as all the data I could find related to the $ value of turnover – which was phenomenal – and not the actual number of Bitcoins traded. Normally, when an asset sees a huge increase in price, this goes together with a corresponding increase in turnover. Clearly this has not happened with Bitcoin – why?

The daily volume in September 2017 when the price was about $4,000 was the same as the start of February 2016 when the price was about $400. I had to create this chart as all the data I could find related to the $ value of turnover – which was phenomenal – and not the actual number of Bitcoins traded. Normally, when an asset sees a huge increase in price, this goes together with a corresponding increase in turnover. Clearly this has not happened with Bitcoin – why?

PSD2 (Payment Services Directive) is an extension on the existing PSD within the EU. The objective is to increase competition in the payments industry, whilst increasing access from non-bank firms. This should lead to standard payment formats, infrastructure and technical standards – at first glance an improvement for consumers. However, there appears to be a particular threat to privacy and the threat of third parties gaining excessive access to personal data.

PSD2 (Payment Services Directive) is an extension on the existing PSD within the EU. The objective is to increase competition in the payments industry, whilst increasing access from non-bank firms. This should lead to standard payment formats, infrastructure and technical standards – at first glance an improvement for consumers. However, there appears to be a particular threat to privacy and the threat of third parties gaining excessive access to personal data.