But on the company side, there are many other challenges to face.

Approval for Participating Accounts

The cash pool bank offering the service will require a duly signed approval from every participating bank account from the account holder that the relevant bank accounts are going to participate in the Zero Balance Cash Pool. In a small pool of bank accounts, the challenge will be limited. However a large pool of participating subsidiaries will require significant logistic challenges to get all required documents distributed, signed and returned to the cash pool bank.

Defining the Cash Pool Master Account

The cash pool bank will need to agree with Treasury which account will serve as the “cash pool master” bank account where all the sweeps (both debit and credit) will be settled daily. If central Treasury has its own bank accounts, it is logical to use them as the “cash pool master” accounts.

Setting Up the Ledger for Sweeps

Because a Zero Balance Cash Pool requires a ledger to register the sweeps as “assets & liabilities”, this ledger will need to be set up and arranged for. In the most simplest form, this can be done by means of a spreadsheet where the daily sweeps are being registered. In a more sophisticated setup the ledger is managed either by the ERP or by the Treasury Management System.

In case the ledger is managed from the ERP a separate company code in the ERP is required for the purpose of registering all the sweeps to the Treasury (or Holding). The bookkeeping will need to be aligned as well when you set up a Zero Balance Cash Pool (with an In-House Bank) since the administration of all the daily sweeps will be at the individual participating bank account level. Each external participating bank account will be directly linked to a unique In-House Bank account.

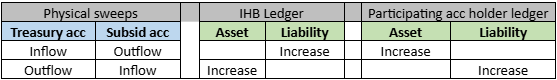

Practically, this register of assets & liabilities will become a structure of internal bank accounts. After, a sweep from the external participating bank account (= outflow) to the central Treasury bank account (= inflow) will need to be accounted for by the central Treasury as an increase of a liability to the participating account holder; and by the participating account holder as an increase of an asset from the central Treasury. Vice versa, a sweep from the central Treasury bank account (= outflow) to the external participating bank account (= inflow) will need to be accounted for by the central Treasury as an increase from the asset from the participating account holder; and by the participating account holder as an increase of the liability to the central Treasury.

Registering Sweeps for Internal Interest Calculations

One of the main reasons for registering the sweeps in a separate ledger is that this In-House Bank register is the basis for calculating and settling internal interest between the central Treasury and the participating account holders. After all, from the Transfer Pricing regulations perspective, all daily cash pool sweeps are considered daily intercompany loans and therefore are subject to arm’s length pricing. In other words, internal interest.

Transfer Pricing and Internal Interest Rate Philosophy

The previous two bullet points can be the reason for setting up a full-fledged In-House Bank function. In conjunction with Transfer Pricing regulations the In-House Bank (IHB) will need to develop a philosophy and strategy for which transactions are going to be “IHB transactions”. In general, this will be the:

- Current account debit and credit sweeps from the Zero Balance Cash Pool,

- Intercompany term loans provided by the IHB to subsidiaries

- Intercompany deposits (aka intercompany Term loans from the subsidiary to the IHB

From Transfer Pricing regulations these transactions will need to be separately priced. These prices will need to be “translated” into a well-founded philosophy for internal interest rates. A few decades ago, you could see that the philosophy was kept simple and standard; debit and credit balances got a margin of 50 basis points on top of an IBOR (Inter Bank Offering Rate). In general, tax authorities were okay with that as they were not really sufficiently educated to understand what a Zero Balance Cash Pool with an IHB structure was all about.

However, these days there is an increased focus on domestic tax base erosions and profit shiftings (= BEPS), which relates to tax planning strategies that multinational enterprises use to exploit loopholes in tax rules to artificially shift profits to low or no-tax locations as a way to avoid paying tax. Due to that tax authorities have become much more educated in various pooling techniques and other transactional activities that an IHB can (or is) initiate(ing). Therefore, tax authorities these days are much more aware of what the setup and implications are of a Zero Balance Cash Pool with an IHB structure.

Hence, guided by Transfer Pricing regulations as developed by the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) tax authorities are scrutinizing Cash Pool solutions with an IHB structure as they review those setups much more critically than several decades ago. This may relate to countries with less developed tax systems; but even in countries with well-developed tax systems, authorities are scrutinizing those setups because of international pressure to adhere to BEPS regulations. Samples are Starbucks in the UK being nailed to the public pillory because of paying less income tax due to profit shifting to low tax countries, and US president Obama calling The Netherlands a “tax haven or tax paradise” because of the favorite tax rulings for Treasury centers in The Netherlands.

In this view, it is noted that tax authorities are also reviewing whether subsidiaries with a bad balance sheet are getting the same favorable interest rates as a subsidiary with an “investment grade” balance sheet. In the commercial banking world, a company with a bad balance sheet (high risk) will get less favorable interest rates than a company with a high-value balance sheet (low risk). An IHB that applies the same interest rate across the board may be considered to be subject to domestic tax base erosions and profit shifting.

Risk Profiles and Interest Rate Adjustments

When setting up a full-fledged In-House Bank, the IHB will need to value its customers based on the balance sheet, its historic development, and its forecast. After all, a commercial bank will assess a company’s balance sheet prior to any form of commitment to lending. A commercial bank will apply different margins depending on the balance sheet and its forecast. Mutatis Mutanda, an IHB will need to apply a similar philosophy to prevent local tax authorities judge the IHB interest rate setup as conflicting with OESD BEPS regulations. Penalties may be applied in several local tax jurisdictions.

Understanding the IHB’s Risk Profile Versus Commercial Banks

Although local tax authorities may scrutinize IHB setups and their interest rate philosophy, local tax authorities will also recognize that an IHB does have a different risk profile than a commercial bank. Key in this is to understand the general relationship between reference rate versus current account interest margin and Term loan/deposit interest margin. The margin distance between debit and credit for an IHB is much lower than for a commercial bank, simply because the margin philosophy from a commercial bank is their business model; for an IHB the margin philosophy is a sophisticated cash management tool (mainly to adhering to OESD BEPS regulations).

By Paul Buck