Managing treasury risk: Commodity Risk (Part IV)

| 14-2-2017 | Lionel Pavey |

There are lots of discussions concerning risk, but let us start by trying to define what we mean by risk. In my fourth article I will write about commodity risk, what the strategies around commodities are and how to build a commodity risk framework. More information about my first three articles can be found at the end of today’s article.

Commodity Risk

Commodity risk occurs due to changes in price, quantity, quality and politics with regard to the underlying commodities. This can refer to both the commodity as a whole and an input component of a finished good. Commodity risk usually refers to the risk in a physical product, but also occurs in products like electricity. It can affect producers, suppliers and buyers.

Traditionally, commodity price risk was managed by the purchasing department. Here the emphasis was placed on the price – the lower the price, the better. But price is only one component of commodity risk. Price changes can either be observed directly in the commodity or indirectly when the commodity is an input in the finished product.

Availability, especially of energy, is crucial for any company to be able to undertake operations. Combining commodity risk over both Treasury and Purchasing allows these 2 departments to work closer and build a better understanding of the risks involved. It also allows for a comprehensive view of the whole supply chain within a company. A product like electricity is dependent on the input source of production – gas, petroleum, coal, wind, climate – as well as the price and supply of electricity itself.

There are many factors that can determine commodities prices – supply and demand, production capacity, storage, transport. As such it is not as easy to design the risk management model as it is for financial products.

General strategies that can be implemented

- Acceptance

- Avoidance

- Contract hedging

- Correlated hedging

Acceptance

Acceptance would mean that the risk exposure would be unchanged. The company would then absorb all price increases and attempt to pass the increase on when selling the finished product.

Avoidance

Avoidance and/or minimizing means substituting or decreasing the use of certain input components.

Contract hedging

Contract hedging means using financial products related to the commodity, such as options and futures as well as swapping price agreements.

Correlated hedging

Correlated hedging means examining the exposure of a commodity – the price of crude oil is always quoted in USD – and taking a hedge in the USD as opposed to the crude oil itself. The 2 products are correlated to a certain extent, though not fully.

Commodity risk framework

Commodity price speculation – most contracts are settled by physical delivery – affects the market more than price speculation in currency markets.

To build a commodity risk framework, attention needs to given to the following:

- Identify the risks

- Measure the exposure

- Identify hedging products

- Examine the market

- Delegate the responsibility factors within the organization

- Involve management and the Board of Directors

- Perform analytics on identified positions

- Consider the accounting issues

- Create a team

- Are there system requirements needed

Problems can arise because of the following:

- Relevant information is dispersed throughout the company

- Management may not be aligned to the programme

- Quantifying exposure can be difficult

- There is no natural hedge for the exposure

- Design of reports and KPI’s can be complex

It requires an integrated commitment from diverse departments and management to understand and implement a robust, concise policy – but this should not be a hindrance to running the policy.

Cash Management and Treasury Specialist

More articles of this series:

Managing treasury risk: Risk management

Managing treasury risk: Interest rate risk

Managing treasury risk: Foreign exchange risk

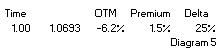

(1.5%, see diagram 5) by the chance it will be exercised (Delta, in this case 25%), ie 1.5% : 25% = 6%. It could be a very disappointing to find that if this Conditional Premium option is only marginally ITM at maturity, because the premium of 6% still has to be paid.

(1.5%, see diagram 5) by the chance it will be exercised (Delta, in this case 25%), ie 1.5% : 25% = 6%. It could be a very disappointing to find that if this Conditional Premium option is only marginally ITM at maturity, because the premium of 6% still has to be paid.

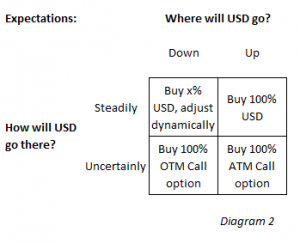

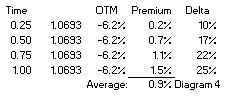

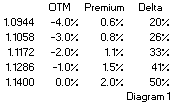

bought the option for 1.5%, we could sell it after 3 months at 1.1% and buy the USD through an outright forward transaction. This approach shows that the net cost of option protection would be only 0.4% (1.5% – 1.1%). Which would be cheaper than the premium of a 3-month option with the same Delta. Also, because the option has a higher Delta than a 3-month option with the same strike (25% vs 10%, see diagram 2), it will follow the spot market much better. The bottom line of paragraph 3 is that a longer dated option can be bought with the intention to sell it again at some point, the net cost being less than buying a shorter dated option. While it serves as a hedge against price changes.

bought the option for 1.5%, we could sell it after 3 months at 1.1% and buy the USD through an outright forward transaction. This approach shows that the net cost of option protection would be only 0.4% (1.5% – 1.1%). Which would be cheaper than the premium of a 3-month option with the same Delta. Also, because the option has a higher Delta than a 3-month option with the same strike (25% vs 10%, see diagram 2), it will follow the spot market much better. The bottom line of paragraph 3 is that a longer dated option can be bought with the intention to sell it again at some point, the net cost being less than buying a shorter dated option. While it serves as a hedge against price changes. buy the 1-year option in diagram 2 for 1.5%. Alternatively we could consider buying a right to buy this option for 0.4% in 3 months time. At that time the 1-year option will only have 9 months remaining, but the strike and 1.5% premium are fixed in the contract. On the expiry date of the compound option we can decide if we want to pay 1.5% for the underlying option. Alternatively, assuming nothing has changed, we could buy a 9 month option in the market for 1.1% (see diagram 2). In such a case we wouldn’t exercise the compound option.

buy the 1-year option in diagram 2 for 1.5%. Alternatively we could consider buying a right to buy this option for 0.4% in 3 months time. At that time the 1-year option will only have 9 months remaining, but the strike and 1.5% premium are fixed in the contract. On the expiry date of the compound option we can decide if we want to pay 1.5% for the underlying option. Alternatively, assuming nothing has changed, we could buy a 9 month option in the market for 1.1% (see diagram 2). In such a case we wouldn’t exercise the compound option. Should we need to exercise the option to get our USD, it still means a combined hedging cost of 3.8%. Which is more than if we had bought the ATM option for 2% premium. Conclusion: Buying an OTM option reduces the up-front cost versus buying an ATM option. But ex-post hedging with an OTM option could result in total hedging cost which are higher than an ATM option.

Should we need to exercise the option to get our USD, it still means a combined hedging cost of 3.8%. Which is more than if we had bought the ATM option for 2% premium. Conclusion: Buying an OTM option reduces the up-front cost versus buying an ATM option. But ex-post hedging with an OTM option could result in total hedging cost which are higher than an ATM option. option is exercised, or the USD must be purchased from the market at the prevailing rate.

option is exercised, or the USD must be purchased from the market at the prevailing rate.

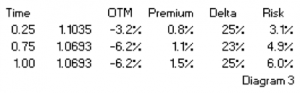

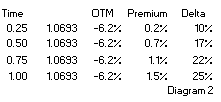

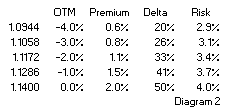

Risk appears fairly stabile across strikes, which makes sense because the premiums are calculated with one volatility on one underlying. The Risk on OTM is lower than that for ATM options. It appears that OTM premiums are relatively more expensive, they give protection against less potential loss.

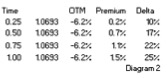

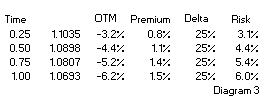

Risk appears fairly stabile across strikes, which makes sense because the premiums are calculated with one volatility on one underlying. The Risk on OTM is lower than that for ATM options. It appears that OTM premiums are relatively more expensive, they give protection against less potential loss. Diagram 3 shows Premiums, Delta and Risk for different tenors. ‘Time’ is the time to expiry of the options in fractions of years. Its shows that for longer tenors, the Risk is higher. But disproportionally. For the same chance on exercise a hedger could double the premium to buy a hedge for a 4x longer tenor.

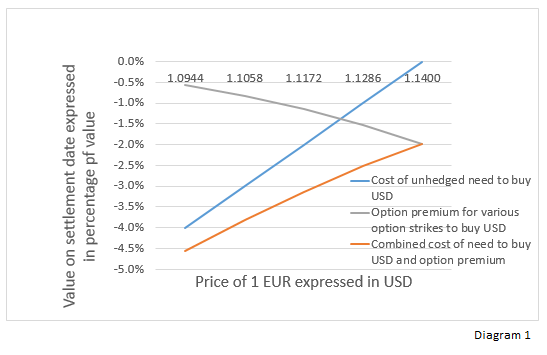

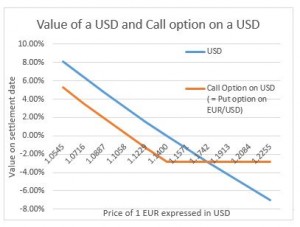

Diagram 3 shows Premiums, Delta and Risk for different tenors. ‘Time’ is the time to expiry of the options in fractions of years. Its shows that for longer tenors, the Risk is higher. But disproportionally. For the same chance on exercise a hedger could double the premium to buy a hedge for a 4x longer tenor. Diagram 1 explains his feelings. I assume he was considering only the left half of the payoff diagram. After an appreciation of the USD, a USD is always worth more than a call option on a USD, the difference being the option premium.

Diagram 1 explains his feelings. I assume he was considering only the left half of the payoff diagram. After an appreciation of the USD, a USD is always worth more than a call option on a USD, the difference being the option premium.