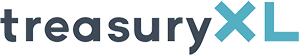

Q&A | LIBOR: The End Of An Era

By Pieter Bierkens and James Leather

Pieter Bierkens (PB) has been at the helm of interest rate benchmark reform for the Commonwealth Bank of Australia since August 2018 till end October this year and served as the chair of Australia’s LIBOR reform working group. In this Q&A, he speaks to James Leather MCT (JL) on the journey to date, the impact on treasurers and what the future might hold.

This interview was first published in The Treasurer

Q&A

JL: Remind us, what was interest rate benchmark reform all about?

PB: After the global financial crisis (GFC) it became apparent that there was a need for risk-free rates (RFRs) alongside Interbank Offered Rates (IBORs) – which are rates, such as LIBOR and EURIBOR – that encompass a bank credit component. That need reflected the fact that much of the market (e.g, cleared derivatives) had become riskfree as a result of post-GFC reforms and risk-free contracts were best served by risk-free reference rates. In addition, LIBOR was no longer fit for purpose and would be discontinued. The upshot was that in LIBOR jurisdictions, the IBOR was replaced by an RFR, while jurisdictions with a viable IBOR (such as EURIBOR or Australia’s BBSW) would continue with both an IBOR and an RFR. RFRs are overnight rates and are typically compounded in arrears over the interest period.

JL: What is the main consequence of the change to RFRs for corporate treasurers?

PB: Borrowing costs will no longer be dependent on the creditworthiness of major banks as there is no ‘credit’ component in the coupon reset. That means that in times of market upheaval, borrowing rates may go down (because overnight rates drop on the back of Central Bank easing) whereas LIBOR rates would probably have gone up, reflecting higher bank borrowing costs. We saw this divergence in the IBOR and RFR rates play out in March 2020, when COVID hit. There is also no ‘reset risk’ in RFRs since the interest rate coupon will be reflective of market observations over the entire interest rate period, not just that on the reset date.

JL: What are the some of the other things to be aware of?

PB: In multi-currency borrowing facilities, some of the interest rate legs may still reflect an ‘IBOR’. That means that some currency legs of your facility may have rates that react differently to economic developments, and in particular, to changes in credit conditions. Additionally, RFRs are typically compounded in arrears. That means that the value of the coupon payment is not known until the end of the interest rate period. In the USD loan market, we are seeing widespread adoption of ‘Term rates’ which are forward-looking RFRs. However, these are not widely used in the derivatives market, which means that hedging such Term exposures may be more costly than it would be for RFR exposures compounded in arrears.

JL: Is the transition away from LIBOR now complete, or could there still be issues lurking?

PB: The LIBOR transition is now virtually complete and once synthetic LIBOR ceases (at the end of September 2024) the few contracts that still reference this rate will have transitioned as well. At that point, the benchmark rate that was once the most widely used reference in financial markets, will have vanished from the screens completely. So, to answer your question, I don’t see anything lurking in the dark. The focus is now on the gradual transition of at least some IBORs to RFRs. While still important, that won’t be as monumental a change as LIBOR was though.

JL: What may then be next in interest benchmark reform?

PB: As mentioned, some jurisdictions reference an IBOR that is continuing. But some of those are now moving from IBOR to RFR. An example is Canada, which is transitioning from CDOR to CORRA. Others maintain an IBOR and an RFR: Australia and Europe are examples. However, over the longer term we are likely to see increased adoption of RFRs in those jurisdictions, particularly in contracts such as multi-currency borrowing facilities, and cross-currency swaps: contracts that have both IBORs and RFRs reflected in them are likely to move towards the adoption of RFRs across the entire contract eventually.

JL: What was involved in the transition at CBA?

PB: What made this transition in many ways unique, was the fact that it was guided by regulatory milestones; it was very much a market-driven transition. In that regard, it is probably not unlike the market-wide transition toward net zero. The key elements of the transition were the calibration of internal systems (accounting, risk and others) for the adoption of new rates, and the redocumentation of legacy contracts to reflect the new rates. Critical for banks and other customer-facing entities was then to make sure the customers were suitably informed throughout the process and received fair outcomes of their contractual transition. Over the course of the programme we, like the rest of the world, had to deal with COVID and the transition to lengthy periods of working from home. Then, given the length of the programme, we had some changes in staffing, but thankfully the newcomers were able to pick up the baton without too much trouble. As with any other programme, there were plenty of challenges along the way. It was critical to understand interdependencies with the deliverables of other programmes and whenever needed, to escalate roadblocks quickly.

JL: Was the implementation of the transition successful?

PB: Very much so; there were no systemic failures and the market functioned very well throughout both the non-USD LIBOR transition (in January 2022) and the USD LIBOR transition (in July 2023). The lack of upheaval was reminiscent of Y2K. Given the size of the change that was involved, the transition was a resounding success, market wide.

JL: Will the new regimes be an improvement?

PB: I believe it certainly will be an improvement. The financial system is now relying on robust benchmarks reflecting actual market transactions and corporate treasurers will no longer be exposed to the borrowing costs of their bank counterparties, as these costs no longer feature in the setting of interest rates. Importantly, the markets for contracts referencing RFRs have proven to be liquid and robust.

JL: How did you arrive at the role of head of Benchmark Reform for CBA?

PB: I am originally from the Netherlands, but studied in the US where I ended up working for Commonwealth Bank of Australia. Having held roles in interest rate sales and management, I moved to the Sydney headquarters to research the impact of global regulatory reform post- GFC. Through that effort, I developed expertise on interest rate benchmark reform and was then asked to lead the LIBOR transition effort of my employer, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia. It was a complex programme and a long journey: five years altogether. The overall process really highlighted the importance of clear communication to, and early engagement with, all the stakeholders, and unsurprisingly, the importance of teamwork. The successful delivery gave a real sense of accomplishment to all involved.

JL: What plans do you have for the future?

PB: I intend to continue working in financial markets, helping stakeholders with the impact of regulatory reform and industry change, wherever it emanates from. After five years of benchmark reform programme work, I may take a short break though!

James Leather

MCT CertBALM® CGMA

Treasury Transformation Specialist

Director, Corium Treasury Limited

James provides interim and advisory services through Corium Treasury Limited. In 2021, he led the UK’s largest commercial property development and investment company – Landsec – through its own IBOR transition.

Can’t get enough? Check out these latest items

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Template_VACANCY-featured.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-06 07:00:522026-03-05 16:03:57Vakanz TMS Project Manager (m/w/d)- Remote (DACH)

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Template_VACANCY-featured.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-06 07:00:522026-03-05 16:03:57Vakanz TMS Project Manager (m/w/d)- Remote (DACH) https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Treasurer-Search-Logo.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-05 16:23:482026-03-05 16:23:48Middle Officer – Transaction Banking @ Treasurer Search

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Treasurer-Search-Logo.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-05 16:23:482026-03-05 16:23:48Middle Officer – Transaction Banking @ Treasurer Search https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Treasurer-Search-Logo.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-05 14:58:562026-03-05 14:58:56Senior Corporate Finance Analyst @ Treasurer Search

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Treasurer-Search-Logo.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-05 14:58:562026-03-05 14:58:56Senior Corporate Finance Analyst @ Treasurer Search https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/GTE-brands.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-05 11:00:552026-03-05 11:34:45Junior Financieel Analist (Cashflow & Forecasting) @ GTE

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/GTE-brands.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-05 11:00:552026-03-05 11:34:45Junior Financieel Analist (Cashflow & Forecasting) @ GTE https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Monex-BLOGS-featured-1.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-05 07:00:042026-03-04 15:54:30March 2026 FX Forecasts

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Monex-BLOGS-featured-1.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-05 07:00:042026-03-04 15:54:30March 2026 FX Forecasts https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Treasurer-Search-Logo.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-04 10:24:192026-03-05 11:34:58TMS Project Manager (m/w/d)- Remote (DACH) @ Treasurer Search

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Treasurer-Search-Logo.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-04 10:24:192026-03-05 11:34:58TMS Project Manager (m/w/d)- Remote (DACH) @ Treasurer Search https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Surecomp-BLOGS-featured-2.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-04 09:00:482026-03-04 07:45:37Surecomp Appoints Ilan Buganim as Chief Executive Officer to Steer Global Growth

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Surecomp-BLOGS-featured-2.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-04 09:00:482026-03-04 07:45:37Surecomp Appoints Ilan Buganim as Chief Executive Officer to Steer Global Growth https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Embat-BLOGS-featured-2.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-04 07:00:212026-03-03 15:58:20Visibility and Governance: How to Prove Compliance When AI Decides

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Embat-BLOGS-featured-2.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-04 07:00:212026-03-03 15:58:20Visibility and Governance: How to Prove Compliance When AI Decides https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Jesper_bLOGS-Expert-featured.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-03 07:00:592026-03-02 16:06:18Working Capital: The Forgotten Lever of Liquidity – and the Lost Treasury Generation

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Jesper_bLOGS-Expert-featured.png

200

200

treasuryXL

https://treasuryxl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/treasuryXL-logo-300x56.png

treasuryXL2026-03-03 07:00:592026-03-02 16:06:18Working Capital: The Forgotten Lever of Liquidity – and the Lost Treasury Generation